A conversation on the long arc of history with “Mother” Mamie Moore

We believe that any vision of a next system that doesn’t ultimately resonate with those working on the ground for economic and racial justice in the communities most marginalized, exploited, and oppressed by the current one is not really getting at what really needs to be next. A big part of this is listening and learning, with humility and respect, to the voices of the people who have been fighting on the frontlines—here, we asked Kate Diedrick of Solidarity Research Center to talk with Atlanta-based community organizer “Mother” Mamie Moore about her trajectory as an activist and advocate for system change starting at the neighborhood level.

Diedrick: Can you tell me a little about yourself?

Moore: You know, I was raised as a southern Baptist in a religious family. My family just went to church, they were Baptists, they were Christians. I was also raised middle class— but we were poor and working class people. We came from Georgia farm people. They came as a part of the Great Migration. My father was a factory worker. My mother was a factory worker. Then she went to beautician school and she became a beautician. Back then that was one of the critical services for Black people—all of the services we could not get from White people, we created for ourselves. My mother was the second Black women to own a small business in our community at that time, which was in Central New Jersey, in Somerville, New Jersey.

We migrated to Manville, NJ, home of Johns Manville corporation, producer of asbestos. The factory workers in Manville were composed of half Black men and half Eastern Europeans. Many of the workers got lung cancer from exposure to asbestos. So my father, two uncles, a cousin, they all died from lung cancer. But as horrendous as they were, these jobs put them in a different economic base. My mother, more so even than my father, operated from a Black middle class perspective: “You’ve got to go college. You’ve got to get an education. This is what will get you out of this mess that Black people are in.” I believed that. So I graduated from high school and went to college—but in between I experienced a date rape and got pregnant. This was 1956 —there was no abortion option. Even if there were, we were a Christian family and so there was no abortion option.

I was ostracized, isolated totally from all my friends. Their mothers and fathers wouldn’t let them relate to me. I was a marked woman. My mother supported me not getting married and going back to school instead. We had to get a lawyer to force the high school to let me come back because I was “an immoral character and could not let me back in with the moral population of the school.” But that’s okay [laughing] because the lawyer got me back into the school.

I did the whole thing. I did the education piece. Got my degree, went on, got another degree in nursing, started working in medical institutions. And all the time you’re facing racism; you’re a registered nurse but there weren’t Black registered nurses back then. So you’re working on the floor and the lab technician comes up to you and asks, “Where’s the registered nurse?”—when you’re wearing a big RN on your jacket. But it wasn’t a matter of fighting back then. Middle class Black people in that period believed that if you got the education, the doors would be opened and you would be accepted into society. All of the Civil Rights stuff was just: you need to stop (fighting), get a job and pull yourself up.

Diedrick: And you believed that?

Moore: And I believed that. At the same time: as I was trying to make it happen, I was still “just a nigga” to white people. And I had no place with the Black community because I was an educated Black person.

Diedrick: And a woman?

Moore: And a woman. Back then I didn’t think about that. The whole time I’m thinking: if I get a little bit more education, it is going to get better. But it didn’t work: I had no relationships, I had no connections in my church. I had no men because, don’t forget, back then if you were an educated Black woman there weren’t very many men who would consider dating you, let alone marry you. That was the myth: go to school, get your degree, get married, get children. I tried two years of marriage and I just walked out of the house one day, closed the door and went home [laughing]. I was like, “hey, this was a big mistake, I can’t do this.” It was a despondent, de-moralizing period in my life and I was ready to check out. I was ready to do suicide because it wasn’t working and I couldn’t make sense of it. No sense. “I did all the things you told me to do and I’m still not anybody. I’m just this single Black woman who goes home, goes to work, comes back, gets up, goes home.”

Diedrick: And how did you get out of this place? What led you to start organizing?

Moore: This was the high period for the Economic Opportunity Act. So there was a great deal of activism across the country, from very small communities to huge urban areas, with lots of money flowing down. In my county, Somerset county, which was the 13th richest county in the country, Republican-controlled, they had gotten this economic opportunity money. The laws of the Economic Opportunity Act of 1965 were very rigid—you had to have community participation from the poor. Well, as they do now, they hand picked their poor. But there were these radical, leftist Black men and women in my county who were very smart, coming out of the trade unions but also out of revolutionary West Indian experiences. These radical Black men and their wives were at the front of what was going on in Somerset County at a grassroots level. They were the first in Somerset County who ran independent school board candidates from their neighborhoods. They challenged the system through an electoral process and no one else was doing that in New Jersey at that time.

They put together a strategy to take control of the Economic Opportunity process, which by law had to have elections. So these activists organized their communities to get them elected to the board of this community action program, which had to be 1/3 business, 1/3 community, and 1/3 elected officials. These were smart people, because of what they learnt in the trade unions. Trade unions teach you about bylaws, parliamentary procedure. They knew all that. They knew board control. And the first thing they did when they got there was take control of personnel committee and the by-laws committee. And from there they just took control.

Diedrick: And were you aware of this happening?

Moore: No, no. What happened was: once they controlled the board, there was also this question of who gets on the board. And they went about placing people on the board from a broader base. They sent out a notice to all these churches, and my church sent me to represent them on this board. So, when I got on the board—as smart leftists, you are looking at the class, the skills, capability to use for the revolution. And they looked at me and said “oh, yeah.” Because I was a Black with extraordinary skills. The other Blacks that got elected were poor and working class—they were radical, they wanted to see some change, they wanted jobs and so forth. But they didn’t have the skills in terms of literacy and what I could do. They had a heart for the class. I didn’t have a heart for the class. I was just this middle class Black woman doing this stuff. But this was my orientation, my education to radical politics.

Diedrick: So this group got you a job?

Moore: Yes, a job with the Economic Opportunity Program. I got introduced to organizing, to the class, and I got intentional transformation. . Back in 1969 there was a group that was doing heavy duty Black consciousness raising. They did intensive workshops. You’d go in on Friday and come back out on Sunday afternoon. It was intense. They just stripped you down—asked questions like: who is your favorite keyboardist? [I answered] “Liberace.” Everyone in the room just laughed. I knew no [Black] artists. Knew no Black writers. Knew no history about us as a Black people. The stripping down included “What’s up with your hair?” You know what my hair looked like—it was straightened, like yours. They keep stripping you down, stripping you down, stripping you down. And finally, I got it. I didn’t know any of this stuff. And I came out of this weekend with a hatred; I hated White people so intensely. I just hated them. I realized that I had nothing before I got exposed to this.

They also talked about how capitalism organizes you so that you have no identity, you don’t belong anywhere but in the meantime you are trying to be somebody that you can’t be and it literally makes you crazy. And I could identify with it because I was crazy. I didn’t belong anywhere. I didn’t have any identity. I couldn’t look back to anything. So that became my radicalization and the capacity for these men and women to develop me as a leftist. They didn’t touch my Christianity. They were like, “Oh, Mamie. She’s the one who believes in that God” [Laughing].

Diedrick: But they weren’t leftist Christians. They were traditional Marxists?

Moore: They were traditional Marxists, ideologically, but they were also, the Blacks who did not accept the traditional modality of the Communist Party, which was to use Blacks and have them running around yelling: “I’m a communist,” with [other] Black people looking at you thinking that you’d been indoctrinated. So they weren’t going around saying that. They were just going around dealing with the needs of the people in the community. And the critical piece that they had that the CP didn’t have is that they organized us to build institutions that we controlled. We built within that county, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 corporations, 501c3s that got money. We had a Black library that was registered with the state and the county. We had three youth and community development projects that the youth in those communities (and their parents) controlled. We had a drug rehab program that serviced women and their families, with a board made up of a certain number of substance dependent individuals and their families.

Again, the Economic Opportunity Program allowed us to be able to have those kinds of advisory boards. For example, it was mandatory that if you had your child in Headstart you had to attend the policy meetings or else your child couldn’t attend. It was all structured, policy-wise, around community control. Now they’ve stripped all of that out.

Diedrick: And so this work was bringing you to critique the structural issues with capitalism…?

Moore: No! I was just working. I was just doing this thing, and building a personal relationship with the executive director. I knew these folks weren’t Christians, but I didn’t worry about it because I was being fulfilled as an individual and all these gifts I had, I was using them. And meanwhile they were hammering a class consciousness into me. What the director said was: “Mamie, some of the brothers and sisters said you said so and so and so to them. That’s some shit. We don’t do that. Those are the people we are supposed to serve. Now, if you don’t get this together, we can’t use you. So, here’s a book to read.” First one I read was Freedom Road. He gave it to me because I was in this intense space of “I don’t want to mess with any White people.” But he said to me, “Mamie, we can’t build this without white people. There are some good White people. Some of them are crappy, but there are some good ones. So you’ve got to get over that hating white people thing. And I know what you’re feeling because I know where you came from.”

Because he was out of the Great Depression, in reform school at 13, out of reform school when the Second World War was hitting off. His father took him to the recruitment station at 16 and signed him up—and he got shipped to the front of WWII. But he looked up and saw all these Black men boarding this ship to go to the front of this war and said, “screw it”: he left and went AWOL, into an enclave in London that was run by prostitutes. They received all—mostly Black—American soldiers that came in and they took them in. He became a staff person for these prostitutes. Washing their clothes, doing their hair. Whatever they needed him to do. Of course, the MPs found him and he got put in jail.

Diedrick: Wow. What a story!

Moore: But he said that in jail Freedom Road was what he was given. He was so hostile and this white officer said, “Okay. Let me give you this to read.” So that’s how he got his movement into the left. And when he came out the jobs people were getting were in trade unions. So he became a Teamster. Teamsters in the late 40’s, 50’s, 60’s were on it.

Diedrick: Did you consider him a mentor figure?

Moore: Yes. He was my mentor. He taught me all that stuff. And one day he asked me: “You know, who do you think I am?” And I said, “I don’t know. You’re Ted.” And he told me: “Well, no. I’m a communist.” And my heart went [gestures to the beating of a heart]. But then I begin to think: “Oh. I haven’t seen anything but good stuff here. Good stuff for myself. Good stuff for Black people. People are learning how to control their lives. I’m working with these families and their children. They are getting preschool education. People were getting jobs because they were getting empowered. They were learning things. We were bringing in jobs programs. We were bringing in housing programs. And I said, “hmmm. Well, okay.” But of course, what happens is you have to choose which ideology you want. And I said, Ok. This works better for me than what Christianity has done because it has not helped me.

Diedrick: Can you talk about the kind of actions you were participating in?

Moore: We were doing demonstrations against police brutality back then. They were locking up young Black men back then like they do now. And we were going and demonstrating in front of police stations. I’d never done anything like that. My life was right here [draws a small box with her hands]. So, I learned things through experience. It was like: “Okay. There is this white-led training institution that is getting half a million dollars to train poor people. And they ain’t training nobody. We are going to sit in, picket them and take it over—Mamie, you’re in charge!” “I’m in charge?!…Okay…What am I supposed to do?” “You’ve got ten people, take them down there, walk in and take the office over” So that’s what I did.

Diedrick: And it worked?

Moore: I walked in and said, “Get out. Everybody get out.” Closed the door and put a chain around it and we sat down. The state was messing with money—hey wouldn’t give Black communities their money. They’d hold it up. We’d have to fight for every payment we deserved. We’d have to picket the state house. “Mamie, you’re in charge.” “Okay…” [laughing]. We’d go down, fifty people down to the state house with a padlock and a big old chain. “If you aren’t out, too bad. Then you are chained in with us.” [Laughing].

So, everything that I learned was through that kind of experience, through doing it, and then the reading and educational piece. You don’t have to say to people: “You gotta be this.” But what we do have to say to people is “It’s not you. You are not the problem.” Because that’s what I learned: I wasn’t the problem. There wasn’t anything wrong with me. There is racism and it’s real and Black people are excluded. I learned about its historical development. I learned about how it was part of deliberately institutionalized in the constitution, to make money, to build this country. I learned all that stuff. I learned capitalism. I learned socialism. There are different systems that make this world work. It’s not accidental. This is how it’s organized. But also, what I got was a love of the class. That no matter where I go, I’m in the fight for the class. I’ve lived in [New Jersey, Virginia, Atlanta], Chicago, I’ve lived in Columbus, Ohio. And everywhere I go I sit down, get to work, get busy. See who is abusing the class and get in that fight.

Diedrick: And would you say that your focus in those cities and times was in building institutions?

Moore: Wherever I could. Yes. This was the period after Ted died. I had to choose again what I was going to do. I had to decide whether I was doing this because I loved this man or I was doing this because I was a real revolutionary. And I said: I’m a real revolutionary. If he dies today, I’m a revolutionary and I’m going to be a revolutionary. And that choice enabled me to be able to say, when he died: “Okay, where is the revolutionary place that I need to go?” That’s how I ended up in New York, organizing around independent, third party electoral politics. I joined the group that Ted and I had worked with to build an independent trade union for day care workers, a workforce that was un-unionized and abused.

One of the things that I’ve learned is that progressive organizers, Black, White, Latino, Native American, gay, straight, etc have a different perspective on empowering the poor by enabling them to build institutions/corporations that they control. For organizers in the 60’s through now, building community controlled institutions was not viewed as a means of changing the conditions and lives of disempowered communities. We built institutions with the working and non-working poor. For us that was empowerment. It’s an ideology that you walk with—but that ideology is also tied to your capacity to be able to continue to mobilize the class in a way that moves them.

Diedrick: Were you working as you do here, in different organizations with different roles? Or was the Black Marxist, nationalist organization, was that the central space from which you were organizing?

Moore: Yes. We worked with different organizations to win their support for parent empowerment in head start, passage of universal child care legislation, building a child care workers’ independent trade union, advancing legislation that supported the anti-poverty movement,. We were part of the leadership that organized New Jersey anti-apartheid forces and the New Jersey women’s political caucus. I was a founding member of the New Jersey and national WPC. No, we were not a nationalist organization. We were Black men and women with a Marxist ideology which calls for a coalition politic.

Diedrick: What was the name of your organization?

Moore: Didn’t have a name. Didn’t need a name. We built institutions.

Diedrick: So the leadership was on the same page: building institutions, building power, creating opportunities for education?

Moore: That’s right. And finding leaders within the communities that would come forth and lead those institutions, okay? What we believed is that a radical view and understanding of how the system worked would systematically build a revolutionary base that could bring in a new social system.

The authorities were charging us with being these radical communists—the county commissioners were always trying to get us, and we experienced major attorney general investigations, FBI investigations—there were all kinds of investigations. But what we had which not everyone has today was a very tight organization that was fiscally accountable and programmatically accountable. If the government said, “do a-z,” we did a-z. And we had one of the most progressive child-care programs in the state.

This is something today’s 501c3 corporations have to learn. I came here and people are doing stuff and I’m saying, “You are not going to be able to keep money doing that, baby.” You know? “Where are your books? Have you filed with the state?” Our neighborhood association [in Atlanta] was getting ready to lose its certification because nobody had paid the state certification for two years. “Did you do your 990?” You know what I mean…

Diedrick: So it sounds like [for you] building alternatives is working within the systems that exist in a tight, organized way [laughing]?

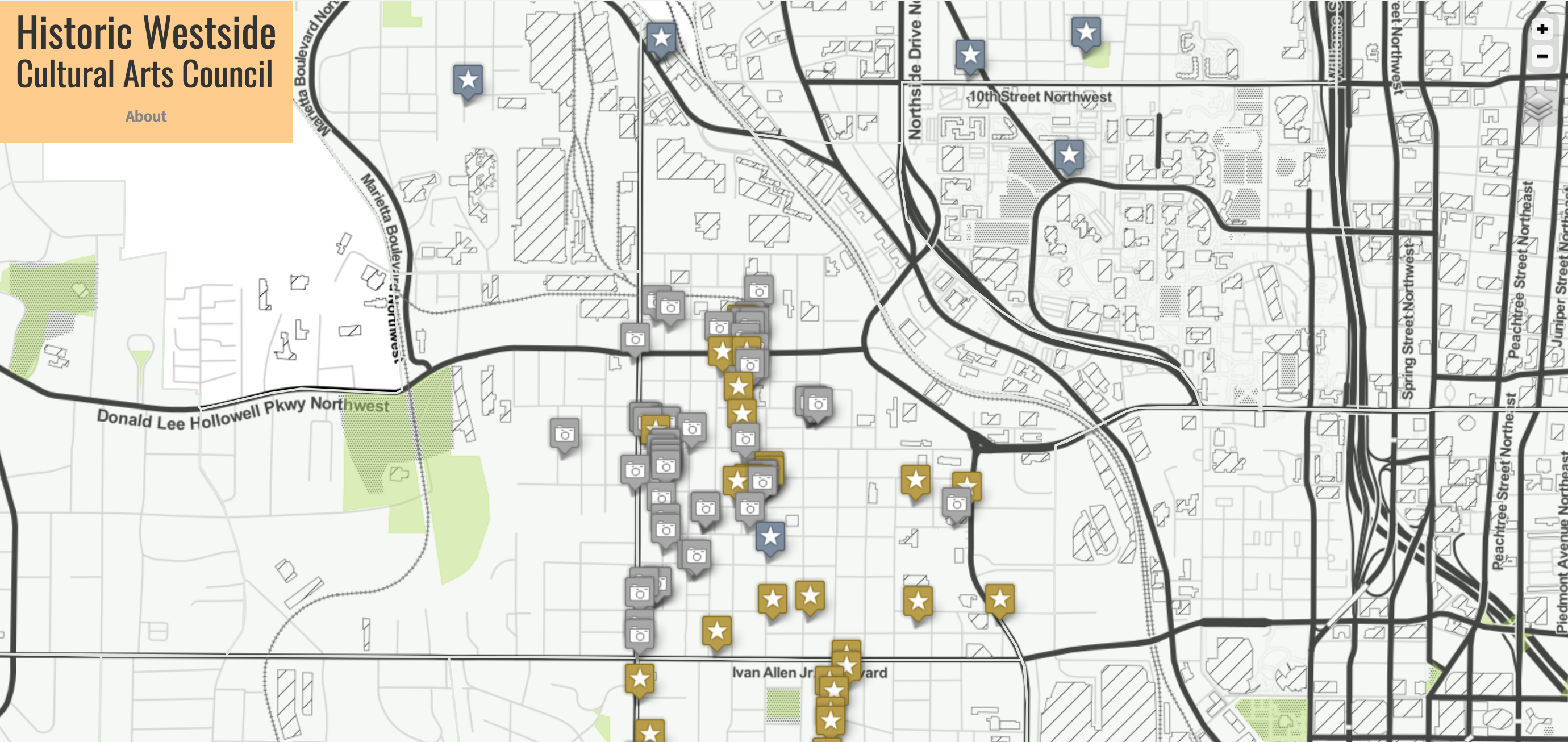

Moore: Yes. All systems are organized around corporate structures of some sort. So, the organizing that I am identified with is that of building our own community controlled institutions. Look at the the Festival of Lights [community festival, one program of the Historic Westside Cultural Arts Council, a 501c3 that Mother Moore co-founded in English Avenue, her neighborhood in Atlanta]: I told Tracy [friend and founding president of the board of the Historic Cultural Arts Council] from the beginning, “if all you want to do is do a festival every year, I am not in for that.” But what we can do is we can do the festival and then evolve into a 501c3 cultural corporation. Tracy said yes. Because folks are not familiar with the power of non-profit incorporation, the doors that are open for funding, etc. There is tons of money culturally. As poor communities of color, we don’t know nothing about non profit corporations and funds that support the work of these organizations. We don’t know how to organize ourselves to get it. When we finished the first festival, the very next year we had a corporation.

Diedrick: Could you talk about how your relationship to your faith has changed over the course of your organizing career?

Moore: I was a returner to Christianity because I saw in Virginia that this preacher that I was working with was a powerful, independent leader. I said, I’ll join his church and I can organize him. That’s what I was thinking. I wasn’t thinking about God at the time. I was thinking about organizing this preacher to be a revolutionary leader in Richmond. But these were phenomenal people. These were phenomenal Christians. They lived what they believed and they didn’t care what my worldview was. They just loved that I cared about the poor people in Richmond. And they were so glad I was in their church because they were a church that was in the street. They were doing education and organizing in their own way, to educate people about housing issues. They were fighting with the city about what kind of service they had for the homeless in the city. And that was how I got related to them.

The pastor eventually got fired for all of this work, and he said to me, “I decided that I should follow my calling which is no longer there with them.” So he called me up and said, “What are you doing, having some coffee?” I said, “Yeah. I’m having some coffee.” He said, “I’m starting this ministry. It is going to be organizing in the poor community. You’re an organizer, will you work with me?” And I said: “Hell yeah, I’ll work with you. What are we going to do?” So I got introduced to a Christian base of people that were really radically doing things for the poor in the community. Which is what my passion is: Where’s the class? Who is doing what for the class? How do we work together ? And even in the days with my original revolutionary group, that is what we did. We worked with churches; we worked with women’s group. Remember when they started the women’s political group to get more women elected? I got sent to that. I went to women’s group meetings to organize the women to support universal childcare. I was working with women back them. Getting them organized and saying to them: “You gotta do policies that relate to poor and working class women. This stuff you are talking about? This is all y’all White women. Rich, White, middle class women. What are you going to do for poor, working class women of color? Are you going to support daycare? I know you all don’t need it but they need it.”

Diedrick: Were there ever any problems reconciling faith and revolution?

They got a little nervous when I led the gay pride march and I was on the front page of the Black newspaper. My pastor said, “Mamie, what does that mean?” I said “that means that I am pro-gay and I have to fight for their liberation and empowerment as well as poor Black people. Isn’t that what Christians are supposed to do?” And he said: “Welllll.” He said “Okay. That’s where you are?” “Yeah, that’s what I do. Is that against Christianity? This is who I am. This is why you asked to work with me. I’m a revolutionary. I’m in the street, pastor.”

The key thing is knowing that you need a worldview. And that is what is so challenging in the organizing now. People have worldviews but they don’t live by them. They are Christian but they don’t live by it and they don’t know how to make it work for their lives. I say, “you know, I come from a place where it didn’t work. Christianity didn’t work for me. God didn’t work for me. And I went off and did this worldly stuff. So, God, for me is a God that kind of let’s you go and do and keeps giving you choices. So I was given a choice. I was given a choice for Marxism. I had to choose.

I think the most tragic thing for me is people who have no worldview. Because they have nothing that inspires them to take the world on everyday. The radical, revolutionary brothers and sisters, if they could just get more ordinary and just go and find the brothers and sisters who are lost and suffering and just give them something to believe in.

This is why I’ve been doing the cultural piece here in Atlanta. When I got here.I saw a lot of people who hate their communities—they hate themselves. And I get that. I hated my community, I hated my Black people and I had no place. And I was given a chance to learn about myself and to choose a worldview that empowered me and enabled me to live as a productive, contributing, confident human being in this system. It is very, very hard to live in capitalism if you are not a capitalist or some other worldview. But if you are floating around with no worldview and you are not a part of capitalism, you’re in trouble, because the majority of people in the capital system in particular, are not organized to be capitalists, they are organized to be tools for capitalism. They are not capitalists, they are fodder for capitalism.

The situation today isn’t all that different than during the Great Migration, when Blacks left the south: They get up to the North, they can’t get jobs, they are in bad housing, and discrimination still reigns with another face. I say to myself sometimes: there were no trees to hang them on so they had to find another way to lynch. Job discrimination, housing discrimination, redlining, whatever it took. Ok? You don’t have to redline in rural areas of Georgia because the system is so entrenched. Black people stay where they are supposed to stay, White people stay where they are supposed to stay. Look at Arkansas. Charleston. Are you kidding me? It’s the 21st century and y’all are living with that? Look at middle class Black people who still raise their children to believe that if you get the education, the doors will be opened and you will be accepted because we are now in a “colorless” society. In the meantime, Black young men, educated and uneducated, are being shot down in the streets by the police.

Diedrick: Could you talk about the trajectory of Black social movements? How did we get from the movements you worked with in the 60’s and 70’s to where we are today? How does this play out in Atlanta?

Moore: From our movement to the Civil Rights Movement to the Black Panthers to SCLC, we did a piss poor job of developing the next line of leadership with the right ideology. The ideology of Atlanta is that being a Black elected official—that is a big thing: “they are going to take care of us. Don’t worry, you don’t have to do it.” They don’t—and yet we still idolize them. That is still the way. Get Black people elected. It’s not about empowering ourselves—we’ve got elected officials. That’s not what Dr. King was saying on the eve of his death; he was saying, the radical work we’ve been doing with Civil Rights now has to go over to the economic arena. And that fight has to continue in there, with the class. Nobody picked that up.

I think that church leaders are doing what they think they need to do in terms of their fights for rights, justice and righteousness. But I think we are in a period in which the base of revolutionary activity has not been stirred up. Because we haven’t organized in that base.

Who is moving to stir up the base of the class? If you look around the whole country, the revolutionary activity—and when I say revolutionary activity, I mean challenging people to see the world as it really exists and understand why you are living the way you are living, why you are experiencing what you are experiencing in terms of systems. I raised my two daughters to know systems. But I also told them, you can choose. You can choose to be a Marxist, you can choose to be a Christian. You can choose to be nothing. But at least know the world you are living in and why you are experience what you are experiencing.

Diedrick: I see the system challenges are huge. But you are still fighting, working and building here. So what do you see as the hope? What is your approach here, now?

Moore: What I see as the hope is that I am still operating from a revolutionary perspective. You know? I have a Christian worldview but that has not altered the reality with me that I live in a capitalist system. I do not believe that God and Christ intended for us to live like this. You do not have to be a radical leftist to believe that you are not supposed to live like this. I believe that as revolutionaries, we have the responsibility to keep putting this out. That is what I do. That is what I did when I step forward to intervene in the stadium deal here in Atlanta—I was part of 5 residents of English Avenue and Vine City who filed a lawsuit against the City of Atlanta to stop them from giving the Falcons [NFL football team] 200 million dollars to help them build their stadium, without any agreement to give a percentage of the profits back to the city and to our communities.

Did I think we were going to win? I held high hopes for always winning. But the thing that I knew was key was the education of our people was critical in this. To start the dialogue that this aint “all that” with the stadium coming here.

Everybody says “It don’t make no difference. They don’t care.” But I disagree with that. I think you don’t know the impact of a poor, elderly, working class Black woman standing up against the Falcons in this city. And that’s what I was taught. You have got to stand up because you don’t know what the class will respond to at any point. Russian revolutionary history talked about the spark. All you need is the spark. So, that’s what I am about. The Historic Westside Cultural Arts council is a way for me to be able to do the piece of changing people’s view of themselves, gathering pride. Because if you don’t have that then you don’t even have the capacity to be able to stand up. You’re nothing. “I’m nothing. I made no contribution My family made no contribution. I’m nothing.” But what we are able to do is to bring them in and tell them, “You’re somebody and you have a voice.” No matter who you are, you have a right. You are a prostitute on that corner? You still have a right to say something about what oppresses you. Your means of employment does not deny you of your constitutional right to reject oppression. And so those are the kinds of commitments that I’ve made with my life.

I lived my life standing up for people. And people followed us because we were fighting for justice and equity and the real application of the thing we call a constitution. White people, Black people, middle class people, straight people, gay people. In my organizing I pulled people together across all of those lines simply by saying: this is what we believe is unjust and inequitable and it’s a lie—and we want to know if you want to move over here to something that speaks better to people.

I agree with “The Next System Project statement: “Today’s political economic system is not programmed to secure the wellbeing of people, place and planet. Instead, its priorities are corporate profits, the growth of GDP, and the projection of national power.” It is true that “We can’t go on like this.”

I see this where I live now, in English Avenue, one of Atlanta’s culturally richest historically Black communities, which is also the city’s economically poorest, where the median household income hovers around $21,000. I have spent my life trying to organize and empower working class communities of color around the country—teaching people about the systems they are a part of and working to build alternatives. The critical question for me is: are progressives ready to abandon the current system and forge a direction for political change that creates an equitable and inclusive system? I believe we can achieve this victory. I know that my people who are at the bottom with me are ready for such a change.