On May 9th, 2017 the Next System Project’s Cecilia Gingerich spoke with Alicia Wilson, Executive Director of La Clinica del Pueblo, a health organization based in Washington, D.C. that has served the city’s Latino and immigrant populations for more than three decades. The interview covers the inspiring history of La Clinica, some of the great work the organization is current doing, as well as some of Alicia’s thoughts on health, the current healthcare system in the United States, and the alternatives we need.

Esta entrevista está disponible también en versión española.

Cecilia Gingerich: We are in La Clinica del Pueblo, a health organization based here in Washington, DC. Can you tell us a bit about the organization’s history, and its mission?

Alicia Wilson: La Clinica was founded in 1983, and was really born out of protest. The concept of La Clinica was hatched during a hunger strike in front of the White House on the first anniversary of the assassination of Archbishop Romero in El Salvador. There was a recognition that the US government was fomenting a war that was causing a huge refugee crisis and not providing any basic care for those refugees once they arrived and, in fact, was actually deporting them back to an active war zone. So La Clinica was hatched as a healthcare response to the refugee crisis, and also came out of things like the sanctuary movement, which was, again, a very countercultural response to the official government action and reaction causing a crisis.

It started as the brainchild of a group of hippies that lived up on Park Road in a commune. They hatched this clinic in collaboration with CARECEN, the Central American Resource Center. They did a lot of really visionary things in their first year and one was to say this really shouldn’t be our project, it should be the project of the people that we’re serving, and very quickly they worked to extract themselves from the development and running of this clinic, to truly make it the Salvadoran people’s clinic. This is the refugees’ clinic. It’s always been a collaboration of folks from this country and folks who have recently immigrated from, mostly, Central America, to address the unique and specific health needs of the Central American refugee community.

We grew organically meeting patients’ needs. When patients showed up with cuts, we put Band-Aids on them; when patients showed up with PTSD, we started providing mental health services; and when patients showed up with HIV, we launched HIV care. As we’ve grown and become more sophisticated, a lot of our programming has been developed because patients developed it. Both hiring patients, once we were able to hire staff, and employing Promotores de Salud—or health promoters—and training them. We were one of the first organizations on the east coast to officially train promotores. We combined this concept of the community driving its own solutions—community meeting its own needs—and bringing in support from the mainstream (from US-based churches, church leaders, medical students). The community, and what it needs, has evolved since the early 80s, and our organization has evolved as a result. Now we’re much larger.

Another thing on this line of our trajectory and growth as an organization: we really were developed as a parallel healthcare system because the mainstream healthcare system didn’t serve the needs of this community and, over the years—and certainly in the 90s in particular—we started to recognize that. We needed to bend toward the mainstream healthcare system and we needed the mainstream healthcare system to bend toward our way of doing things. Initially our role in protest advocacy was human rights protests, and became more and more healthcare related advocacy for a more just and equitable healthcare system to serve the needs of the Latino community.

We were a big part of the development of the DC Healthcare Alliance, and I really view that as bending the healthcare system towards the needs of this community. By training promotores and doing the work to educate more broadly about language access and cultural competence we helped to ensure that system wide, not just our clinic, the complexity of immigration and immigrant health needs—and, in particular, Central American and Latino immigrant health needs—were understood. Now we’re pretty mainstream in a lot of ways, in that we’re a Federally Qualified Health Center—we have this sort of federal government Good Housekeeping seal of approval. But we’re also still pretty subversive in trying to say like, “That’s great, and here’s all this other stuff that we do.” Or, “that’s really great because it allows us a platform to do X, Y, and Z.”

We describe ourselves in different ways in different times, but one of my favorite ways to describe La Clinica now is that we’re a community-based organization that does health as opposed to a healthcare organization that might be based in the community. We have a lot of services that are inward focusing—like our patients, their health, their outcomes, their mental health, their needs—and we have our community level, more public health strategies. We tie those two things together so that what happens in the community informs what happens in our clinic, and what happens in our clinic informs what we’re doing in the community. The strategies and techniques for success in those areas can sort of crosspollinate, but the intersection of immigration and health right now is really bringing those things into bold relief, along with the need to have cross-cutting strategies that are looking at how we provide immigrant health, and what does immigrant healthcare mean, and what does it mean right now.

Community-Centered Healthcare

Cecilia Gingerich: I think you just covered this a bit, but in La Clinica’s literature I noticed the term “culturally competent health resources,” emphasized several times. Can you clarify it’s meaning, and how it relates to La Clinica’s work?

Alicia Wilson: At La Clinica, it is largely crafted as understanding where patients come from culturally, historically, and socioeconomically, and giving them a role in determining what they need and what they receive. These days, the big buzz words are social determinants of health and that you understand that somebody who’s walking into your exam room is walking in not just as an individual with some organs and a disease, but that they’re a person who has a history, and culture, and that all that determines how healthy they are right now. You have to have the cultural competence to be able to navigate them towards how healthy they want to be in the future. But, more specifically, for us, cultural competence means whenever possible, hiring from the community that we serve, training staff to understand the context of immigration, training staff and patients to understand the systemic aspects of health and how that’s all interrelated, and taking a bigger picture view of healthcare.

My classic examples are in mental healthcare. If you have a mom and a teenager who are struggling because the teenager is acting out and the mom doesn’t know how to manage it, you need to have the cultural competence to understand their patterns of migration—that the family was separated and when they came back together, the child was with grandma for 10 years and is resentful of mom. And had to fight off gangs, and then had a terrible migration process, and then showed up with mom and mom’s got two kids with a new husband that she doesn’t know. And that kid has to go high school, and has to navigate puberty. There, cultural competence is essential.

Or, in our diabetes and nutrition work: understanding food related behaviors that are cultural. You can’t just say, “You know what you need, is to eat more leafy greens and drink smoothies.” It’s not going to help people. But understanding from a cultural perspective what their food experience is, what their food engagement is, and how much time they have to catch a quick meal when they’re say, in between two jobs, helps you then figure out how to provide the type of healthcare that’s going to lead them toward reducing weight and managing diabetes. The easiest and most straightforward way is to hire from the community, and while that can’t always happen, it’s really the bedrock, I think, of our cultural competency. Then there is training and expertise that starts from there, and the practice of really, really listening to patients, and incorporating them in guiding the service provision as well.

Cecilia Gingerich: Great—local hiring is also something we suggest for healthcare institutions in our healthcare engagement work at The Democracy Collaborative. It’s great to hear about that. How many clinics do you have in the DMV area?

Alicia Wilson: We now have two health centers and then four other sites where we’re proving health related services, but not medical care. This is sort of our flagship clinic, and then we recently opened up new clinic in Hyattsville, Maryland. We also have two HIV prevention related sites that are LGBTQ safe spaces. One in Langley Park that we just opened and one on Mt. Pleasant Street. We have a school-based mental health program at a high school in Hyattsville, and we are also opening a new site that’s going to be the hub for a lot of our community oriented programming that will think beyond the traditional healthcare concepts to looking at art and music and lecture series and all sorts of things, including advocacy and community organizing, and other things that aren’t directly tied to a doctor’s visit, but help to cultivate a healthy community.

Cecilia Gingerich: The community programing sounds great! One of the programs that La Clinica currently provides is the Entre Amigas (Among Friends) program. Can you tell us more about the program, and how it addresses domestic violence within the communities you serve?

Alicia Wilson: Our Entre Amigas program was born almost 15 years ago, with some seed funding to focus on heterosexual women and HIV prevention. It started as a series of weekend workshops for women to talk about sexual health and empowerment and very quickly became a domestic violence program because 80% of the women were experiencing or had experienced domestic violence of some sort.

It has never been officially a domestic violence program—it is a program that is a gender and health program. But the crux of the programming is related to women’s safety and navigating the system towards safety, and the self determination that comes along with it. We toss in some cervical cancer and sexual health awareness and work with an amazing group of Promotoras who are almost all survivors who become peer navigators and peer accompaniers for women who are navigating both the special visa process as well as the local shelter system or restraining order system. It’s an amazing program. We have, I think, over 100 women a year that come through in one form or another.

There are a series of intensive workshops and then a monthly gathering for any woman who’s been part of the program. There are Comadres who are folks who have ten years away from their abusive relationship now, much more stable and strong to provide guidance and support as well as teenagers who’ve been sexual assault victims and everything in between. It touches on trafficking, it touches on the complexity of abusive relationships when you add in the migratory process—if, say, your coyote is also the father of the baby that you’re carrying, who raped you in the process of migration. You have a tie to that person, and how do you navigate all that?

This is where cultural competency is really, really important. And focus on supporting women in what they need right now. It’s also a major medical/legal partnership area for us. We are not legal services providers, but we provide legal navigation support and collaborate with many other organizations who provide services related to domestic violence whether it’s shelters, or legal support, or mental health counseling. A lot of what we do is create the community space for women to share strategies and find support and build community and the accompaniment support of survivors and Promotoras who can really help hold hands when necessary.

It’s gone through a lot of changes over the years, again, really driven by what the women in the group want. It’s been a really amazing journey.

Working in the Current System, and Aiming for a Better One

Cecilia Gingerich: You just mentioned that you sometimes provide support for navigating legal services—do you have any other programming that addresses other (not strictly health-related) structures of the broader system, like policing?

Alicia Wilson: Yes, in our advocacy work, we have been engaged in the sanctuary movement, and how it relates to responses to detention policies. I am actually really intrigued by the overlap between sanctuary cities and over-policing for noncriminal offenses. I feel like in almost every aspect of what we do, we are engaged in a critique of the system that gives rise to the issues. In our substance abuse services, we work with the correctional system, but we also work with the city and spend almost every breath we have saying, “How come there are only three Spanish speaking substance abuse providers in the city, and how come there’s actually no matching or assessment between how many people have addictions and how many service providers exist? How can you build a better system?”

In primary care, there’s so much happening. We do a lot of overlap in terms of how healthcare might be paid for and how healthcare might be provided both at the local level and at the national level. With HIV: How do you really address the unique and emerging needs of young, queer people of color and how do you address homophobia as an HIV prevention strategy? I’m very, very proud of a lot of the work that we’ve done that truly is focused on destigmatizing sexual minorities at the community level as a healthcare intervention. We have about 70 local businesses that hand out condoms on our behalf and encourage people to get tested for HIV. Our work with those local businesses helps normalize HIV and destigmatize HIV, but it also helps destigmatize sexual minorities by saying: “We are not a place that’s standing in judgment of you or casting you out. Here, have a condom.”

Whether it’s a laundromat or hair salon or local auto repair shop on Mt Pleasant Street, they become allies, which makes the whole community a more welcoming space where people are not as marginalized. When you are not in the shadows, you are less likely to engage in high-risk behaviors and you’re less likely to self-harm. That’s a pretty straight line toward reducing overall HIV transmission rates for vulnerable communities.

In language access, we focus on educating hospitals and local providers on Title VI of the Civil Rights Act, which requires language access at these locations. We also educate patients so that they can stand up for their rights, and we also can provide those language services as well, so that people aren’t taking their fourth grader out of school to come to their doctor’s appointment to be an interpreter, but are getting trained interpretation.

I’ve been really engaged recently in racial equity work and in particular, this really cool DC initiative on Racial Equity and the Role of Local Government, which is looking at how DC, in particular, can apply a racial equity lens in its policy making and its program implementation and start to really analyze how policies and structures can perpetuate inequities and perpetuate systemic racism. That can cover policing to schools to streetlights. Once you can get local governments to start to apply that set of lenses to what they’re doing, they can do a racial equity assessment before passing legislation, and determine if a policy perpetuates systemic racism. Then you can start to really deconstruct a lot of those systems.

There are these beautiful models coming out of California and Seattle, and a national group called GARE, Government Alliance on Race and Equity. It’s really cool group. Their tools can be used as a model for how we can push the local government to see what it’s doing to make things worse instead of better—even when they may think they’re set up to make things better (and local nonprofits, also). We can really advocate for diversity and inclusion in a much broader sense than just, “Let’s have a couple tokens on our board.” Instead, they can really look at how they are constructed, and if that structure perpetuates a certain worldview that is not inclusive.

Cecilia Gingerich: Are there any other examples of healthcare systems—or partial systems—in other cities or countries that you look to for inspiration? Is there a particular system that you would like to see us in the direction of?

Alicia Wilson: Oh, gosh. I’m just going to fantasize for a little bit. I would begin again with GARE, from which I’ve learned a lot of really, really interesting things about what is possible—and Seattle is a great example. While it’s not as diverse as other cities, they have been incredibly proactive in making little changes that actually have an enormous impact, and dispel a lot of the accepted mythology about what should be done or who should do what. Really, really thoughtful.

Fairfax County is going through a racial equity collaborative process where they’re looking at the affect of bus routes on health outcomes—how they impact minorities, and specifically how they can recreate segregation patterns that lead to poverty. And they look across sectors, and encourage transportation planners to work with the health department, and housing policy people, and they’re all thinking about racial equity as they’re doing the work. Really cool stuff.

I think what I’ve learned through these efforts and GARE, is that starting at the local level makes a lot of sense—it’s much more doable and it’s really about people in relationships. It’s not about nationwide policy. I mean, when you get to healthcare, name a developed country and I would prefer that to our current model. I am not a healthcare policy analyst, but we have a completely ridiculous system that does nothing but perpetuate inequity and deliver the lowest quality, highest cost, least efficient care that satisfies no one. There are many better models in Germany, France, The Netherlands, Sweden, England, even Canada—you name it.

I think because the US is so decentralized in its management of big things like education and health, and each state really gets to determine how they provide healthcare, there are some really interesting state level models that are worth looking at—but again, it is almost always locality versus state. DC is incredibly progressive. It’s not perfect and it still has a lot of gaps, but it’s a really interesting model for the rest of the country. San Francisco is another. Then, when you get statewide, I think you see some state health directors that are thinking more broadly and asking, “Why are we perpetuating a system where wealthy people get everything and poor people get nothing? And when the poor people get nothing, it’s worse for everybody. Let’s set up a system where everybody gets something and it’s better for everybody. It’s usually cheaper for everybody.”

Cecilia Gingerich: Last week the U.S. House of Representatives passed a bill (the American Health Care Act, or AHCA) that will repeal the Affordable Care Act if it becomes law. If the bill passes as is, how will it impact the community you serve, and particularly immigrants?

Alicia Wilson: The AHCA is sort of a ridiculous bill on a lot of levels. It makes healthcare more expensive for everybody and out of reach for lots. An $800 billion cut in Medicaid has enormous spillover effects on any other safety net program that exists. Because recent immigrants are excluded from Medicaid pretty dramatically, it doesn’t have that one for one effect. But in the District, for example, there’s the Healthcare Alliance. The Alliance is a local program for folks who aren’t eligible for Medicaid, but would be if they had citizenship or legal permanent residency. If Medicaid gets cut, more people spill into the Alliance. The additional demand on the alliance puts greater demand on local funds, and greater demand on local funds means a reduction of benefits and accessibility. It’s sort of a domino in that regard.

The AHCA also undoes parts of the ACA but not all of the ACA. For example, in some cases it leaves mandates in place but takes away the elements by which they were fixed, which leaves all sorts of other challenges—from hospital charity care DiSH funds to prevention funding. Then there are the preexisting condition exclusions. It’s just so ridiculous, and on so many levels, because it allows states to permit insurers to charge more for preexisting conditions not just in the state-based exchanges, but also in private plans. That affects everybody, including La Clinica’s health insurance for our employees—we would have employees who would not be able to afford health insurance. It’s just ridiculous.

There’s also a lot that was in the ACA that is, as far as I know, not totally touched by the AHCA. Everybody’s focused in the ACA on the health insurance exchanges, but there’s tons of stuff that’s not the exchanges, like federally qualified health centers, the CDC’s budget, and infectious disease control. From what I understand, this sort of back of an envelope thing that they cobbled together doesn’t address those things, but perhaps their overall budgeting process would address them and it’s a total crapshoot what’s going to happen in the overall National Institute of Health funding, Centers for Disease Control (CDC) funding. That has enormous implications on vulnerable communities, especially the cuts to CDC funding, which, among other things, funds a lot of HIV prevention work. If all that funding goes away, then what? It could have enormous implications.

Looking Forward

Cecilia Gingerich: Let’s hope it doesn’t go through. But you’ve been with La Clinica for 17 years, and I’m sure have seen some difficult times—what gives you hope for the future, even in the current political climate?

Alicia Wilson:For La Clinica, we were, again, founded at a time when people were getting picked up off of the street and getting deported into active war zones. The awakening of the civil rights and human rights movement toward the needs of this community, I think, has been a very positive move in the right direction. The work of Latino activists to have a seat at the table has been growing over the last 20 years. I think there’s a lot of work to do still so that when we talk about diversity, inclusion, and civil rights, we’re talking about the needs of this community as well as other minority communities and understanding that there are similarities and there are differences and we need to be able to be strategic and targeted in how we address those issues. La Clinica’s weathered lots of storms over the years. I think we have a strong mission and a strong institution.

I also have a lot of optimism around the success of the progressive bubble that we live in. In Maryland and DC in particular, we have pretty enlightened leadership that is generally prioritizing the right things, though we always want things to be better. Our city council is falling all over itself to out progressivize itself. It’s not always perfect and it doesn’t always do things great, but its support for DC as a sanctuary city and support for policies that don’t actively seek to harm people is really good. I think Maryland is a little more complex because of the local and statewide jurisdictions, but in general, the leadership’s headed in the right direction.

At the congressional level, I think it’s a crapshoot. I’m hoping for 2018. Probably the most optimistic thing I’ve read recently was that, if you take the AHCA through the House, get it to the Senate, and the Senate says, “We’re not actually going to look at it, we’re going to write our own law,” and then go through the process of writing that law, and even pass it, and then they have to go through a reconciliation—that means it has to go back to the House for approval. That process could take you right about to October 2018, which is when elections happen. That gives me some hope that we can actually ride this thing all the way to the election and then you can have women who are going through chemo standing in front of their congressmen and being like, “Really?”

I think there is a lot of capacity to advocate, especially around the preexisting condition aspect. Because you know what? Twenty-four million people losing insurance is truly taking away their healthcare. Then you add on whether this could impact everyone with employer-sponsored care? It’d be one-sixth of the US economy that you’re screwing with and you don’t know what you’re doing. Every major medical industry has opposed the AHCA. That’s some serious power if you can get it lined up, and we could have a landslide towards the left.

I guess the other, total pie-in-the-sky hope that I’ve had relates to an article I recently read. It was the conservative case for a single payer system, and really laid out how single payer aligns with a traditional US conservative agenda of efficiency and cost effectiveness and stream lining government and all that kind of stuff. It mentioned that if the auto industry were like the US healthcare industry, to fill up your gas tank you’d have to call Geico to get permission, and the government would have to allow Geico to give you permission to fill up your gas tank. Single payer could take all that silliness and inefficiency away. That’s a very conservative agenda.

Cecilia Gingerich: Do you have any tips for how we can stay healthy in the meantime? Many people are experiencing a lot of stress, which can’t be healthy.

Alicia Wilson: That’s a great question. Speaking as me, Alicia Wilson, and not as La Clinica Del Pueblo, I’d say that dropping off Facebook for a couple months at the beginning of the year did wonders for my mental health, because my Facebook feed was a stream of righteous indignation. That’s just really hard to sustain. If you’re flooded with outrage and indignation all the time, it can be very unhealthy. Unfortunately, I moved to Twitter, which was a different type of righteous indignation. A wonkier version. But it’s a sort of self-care to recognize that the sun continues to rise everyday: yes, we have to keep fighting, but if you miss 30 seconds, the world isn’t going to end.

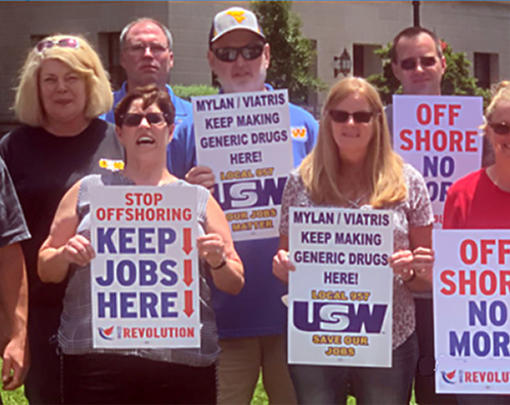

A strategy that we’ve talked about a lot here is to recognize that what you’re doing is the resistance, and get to work. Coming to work everyday at La Clinica Del Pueblo—whether you’re a receptionist or the executive director—is an act of resistance because you are working in a system that is opposing what this agenda is. Doing your job every day is your most successful act of formal resistance, and it’s important to remind ourselves of that if we start to despair. And having opportunities to come together, like going to some marches, can sometimes be helpful too. We have this constant debate about what to do: do you strike, do you march? There seem to be six marches a day in Washington DC, but we have work to do. Though there is some value in coming together with like-minded people and having that sort of cathartic experience of, “I’m not alone!”

It helps to recognize the intersectionality in what we do, and that it’s not just immigrant-serving healthcare intuitions that feel maligned right now. We have a lot of common cause. Allowing those spaces to find common cause, and to just get that tension out and carry a great sign and march—it feels really good. But day to day, do the work because the work is the right work.

Cecilia Gingerich: That’s great. Is there anything else you wanted to add?

Alicia Wilson: When you were describing the work of the Next System Project, I was reminded of one of my senses of optimism right now. Which is that, whatever your diagnosis of the election results, I think there is a major reaction to the class stratification of our country—the widening disparities—and the sense that there is an elite class that rules and everybody else is left to suffer. That was a rejection of the Republican establishment and the Democratic establishment. Whether it is a rejection of the two-party system, or whether it’s a rejection of money and politics, I don’t know, but I think that there is a lot of space for creating new structures because there’s so much dissatisfaction with the status quo as it was prior to the election. Honestly, this president is truly just expanding the privilege of the elite. Is this creating a whole new space for some radical reenvisioning of our system and our structures? That gives me a lot of hope, and the ability to say, “This healthcare system is stupid and the ACA was a heck of a lot better than anything, but it was sort of stupid too.” Why don’t we go for gusto, let’s just do it. Let’s envision a new single payer system because that works and it works a heck of a lot better than anything else that we have.

I’m optimistic that there’s a lot of thinking outside the box happening right now. It’s balanced by this reactive “we have to hold onto the gains we have,” but when you hold onto the gains you have, you also become really entrenched in what those structures are. I think that’s going to be a challenge, but if we can hold onto those gains while also questioning what we really want—I think it presents a great opportunity.